The article briefly describes the life of Nikola Tesla, from the village of Smiljan to New York, from a resourceful boy and animal lover to a world famous scientist. The ancestry of the Tesla family is discussed, starting with a description of the ethnic background of the inhabitants of Lika. Tesla’s education in Croatia consisted of elementary school in Smiljan and Gospic, and secondary school in Gospic and Rakovac. This was followed by the polytechnic school in Graz and further education in Prague. Tesla’s work in Budapest and France, his departure from Europe and the continuation of his work in the USA are discussed, as well as the establishment of his own laboratory. Tesla’s patents in the field of electrical machinery and equipment that he patented at the United States Patent Office are briefly presented. There are also comments by distinguished figures about Nikola Tesla and the recognition he merited

Any discussion of Nikola Tesla always begins with the village of Smiljan, not far from Gospic. The origins of his family were not from that place but from another part of Lika and beyond.

1. INTRODUCTION

Any discussion of Nikola Tesla always begins with the village of Smiljan, not far from Gospic. The origins of his family were not from that place but from another part of Lika and beyond.

Data on all the families who lived in the various parts of Lika several centuries ago have been studied but the name Tesla is nowhere to be found. It was merely the nickname given to one of Nikola’s ancestors, actually named Draganic, who most likely came to Lika from the surroundings of Ledenice. He married into the family of the Orthodox priest Mandic and thus began the Lika family of Tesla.

Nikola’s father was also a priest. After serving in Senj, he came to Smiljan, where Nikola was born and then attended elementary school, which he continued in Gospic. The fine secondary school in the Croatian Military Border town of Gospic and the education Nikola obtained there provided a solid foundation for his further studies. Nikola’s natural affinity for technology was significantly fostered and enriched by his schooling at the secondary school in Rakovac (near Karlovac). Undoubtedly, Nikola’s education at the secondary school in Rakovac had a crucial role in the selection of the profession to which he devoted his life – electrical engineering.

The polytechnic school (Teschnische Hochschule) in Graz, by virtue of its relative vicinity and tradition, was the place the young Tesla aspired to attend in order to acquire knowledge in the field of electrical engineering.

While in Budapest, Tesla’s fertile imagination led to his fundamental discovery in the area of alternating current. His departure to Paris, work in Strasbourg and final transition to New York accelerated Tesla’s professional and scientific activity in the growing field of electrical engineering.

There followed discoveries, inventions, new constructions and patents of enviable quality and frequency. His own company, his own laboratory, many associates and lectures, articles and travels became the daily events of Tesla’s life in America.

However, a fire in his laboratory, Tesla’s disinterest in money, and extensive plans and projects caused him grave difficulties. The years passed, he somewhat changed his area of investigation, his financial situation worsened and his health failed. Thus ended the life of our world famous figure in electrical engineering and science, whose works have immortalized his name and are a credit to his homeland.

2. THE INHABITANTS OF LIKA AND THE ORIGINS OF THE TESLA FAMILY

During the time of the Turkish penetration into the region of Lika, Podgorje and the Senj littoral, in approximately the year 1520, many of the local inhabitants fled the Turkish invaders to safer regions. Croats and some of the old Balkan inhabitants, the Morlachs, Lachs and Olachs, remained in Dalmatinska Zagora and Lika. Part of this population accepted Orthodoxy and part the Islamic faith. These indigenous converts to Islam later intermarried with the Muslims who arrived in Lika from western Bosnia, where the majority of the indigenous Catholic and Bogomil inhabitants had converted to Islam. The Turks brought in Orthodox settlers from Podrinje, Poibarje and Polimlje to settle the regions that the indigenous Catholic

population had fled.

In the parts of Lika that the Turks could not conquer, there dwell what are today the only direct descendents of the pre-Turkish population in these regions. These indigenous inhabitants remained in the old Gacka and Brinj County, Senj and the surroundings of Senj, not far from Ledenice.

When the Turks left Lika, following the peace accord of 1699 in Sremski Karlovci, in addition to the remaining Catholic settlements there were also some Orthodox settlements. The inhabitants of

Lika called them “the people of the Greek rite,” i.e. Orthodox, Vlachs, and the Serbian Orthodox Church

conferred Serbian nationality on them.

The origin of the Tesla family has neither been sufficiently investigated nor is there reliable information. It is known that some of Nikola Tesla’s ancestors had the surname of Draganic. This is a surname that is found in central Dalmatia, and in the 16th century was also the name of parts of the Vrancic family who lived in Sibenik.

According to family lore, one of the ncestors had prominent front teeth that resembled tesli, tools for processing wood. The word tesla, or ax, is found in a famous dictionary entitled Dictionarium Quinque nobilissimarum Europae lingvarum, Latinae, Italicae, Germanicae, Dalmaticae, et Ungaricae, compiled by the Croatian polyhistor Faust Vrancic (Sibenik, 1552 Venice, 1617) and published in Venice in the year It was after this tool that a branch of the Draganic family received its nickname, which later became the surname of Tesla.

In the 17th century, the Draganic family probably arrived in the Divoselo region of Lika from the village of Ledenice near Novi Vinodol, to which they had emigrated from central Dalmatia. It is not known whether some other Draganic received the nickname of Tesla while still in Ledenice.

During the period when the French established the Illyrian Provinces (1809-1813), the senior Nikola

Tesla, the father of Milutin Tesla (1819-1879), served for a time as a sergeant, i.e. a noncommissioned

officer in the infantry of Napoleon’s army, where he was decorated for bravery. It is likely that he had

previously been a soldier in the Austrian army, i.e. in the Military Border Territory in Croatia. According

to family lore, the sergeant’s father lived for 129 years. He made his home in Raduc and probably had

many children. His descendents are today’s Teslas of Raduc.

The wife of the senior Nikola Tesla, Ana, came from a family from the Military Border Territory, a group of Orthodox inhabitants of Divoselo in Lika. Their son Milutin was born in the village of Raduc. Milutin attended German elementary school in Gospic, followed by military school. However, life in the army did not suit him so in Plaskome he studied theology, which he completed in 1845. He then married Djuka Mandic (1821-1892) of Tomingrad near Gracac.

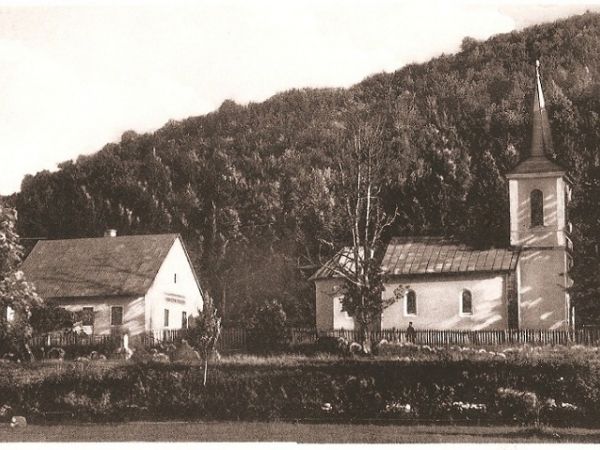

As a young priest, Milutin Tesla served in Senj, from which he was transferred to administer the parish in Smiljan, a village not far from Gospic. On July 10, 1856, Nikola Tesla was born in Smiljan in the house shown in Figure 1, and was later followed by a sister, Mandica.

3. TESLA’S SCHOOLING IN CROATIA

Nikola completed the first grade of elementary school in Smiljan. At the time, the school was attended by

the Smiljan families of Milkovic, Kovacevic, Rudelic, Tomljenovic and others. My grandmother, Marija

Milkovic was in the same first grade class as Nikola Tesla, who was already a boy who liked toys of a technical nature.

In 1862, following six years of service in Smiljan, Milutin Tesla was transferred at his own request to Gospic. Thereafter, Nikola attended the preparatory elementary school in Gospic, which he completed in the year 1866. Even as child, Nikola loved animals. He cared for tame pigeons, as he did in New York until the end of his life.

Nikola demonstrated his resourcefulness in Gospic when a new firefighting hose malfunctioned on the occasion of its official trial. Little Tesla quickly understood that the pipe conveying water from the river was blocked. He felt for the suction hose in the water and found that it had collapsed. When he waded into the river and opened the hose, water rushed forth.

After completing elementary school in Gospic, Nikola attended the lower secondary school where he acquired a good foundation in the natural sciences and learned the German language.

Tesla constructed a water turbine and performed experiments in the field of electricity with the help of

equipment from the school’s physics laboratory. He was interested in mathematics but freehand drawing was not an easy subject for him. He read a lot, borrowing his father’s books. He was an average student but enjoyed calculation so that he was able to compute complex bills in his head.

In the summer of 1870, when he had completed the third year of the lower secondary school in Gospic, he had to remain in bed for two months due to illness. After that, he was sent to recover at the home of his uncle, Toma Mandic, in Tomingrad.

The upper secondary school not far from Karlovac, had been established for the needs of the Military Border Territory and for preparing students for the study of technology. Starting in the academic year 1869/70, the government introduced a final examination at the secondary school in Rakovac, so that it was no longer necessary to take an entrance examination (Aufnahmeprufung) in order to enroll in further technical studies.

In 1863, the Ministry of War in Vienna appointed nine teachers to the higher secondary school in Rakovac, including Martin Sekulic (Lovinac, 1833 – Zagreb, 1905), until then a teacher at the lower secondary school in Rakovac, who taught mathematics and physics. Martin Sekulic was the custodian of the school library at the time.

In 1866, the teachers at the secondary school in Rakovac were given the title of professor. During the

1871/72 academic year, Prof. SekuliÊ taught the subjects of mechanical engineering and arithmetic. The language used in the classroom was German. Tesla always received the highest grade.

After Nikola completed the third year of the lower secondary school in Gospic in 1870, his parents sent him to the higher secondary school, and afterwards to the secondary school in Rakovac. Here he lived

with his aunt, Stanka, who was married to a retired major in the Austrian army, Danilo Brankovic. His aunt was careful about his nutrition and attempted to kindle Nikola’s interest in art and history, without

success. Although he had a sensitive and good ear, he never showed an interest in music.

Nikola was constantly thinking about some invention. On a wagon trip from Gospic to Karlovac, he told a friend that he was working on an invention that would make it possible to transmit speech between Europe and America without any material connection, i.e. without wires or cables.

At the secondary school in Rakovac, he was not a particularly good student. Although he always passed his courses, he usually received barely passing grades in drawing. He was of delicate health and was absent for two months due to illness during the 1872/73 academic year in the first semester of his seventh year of studies.

In 1870/71, he attended the fourth year of studies. The next year he completed the fifth and sixth years of studies. He had an average grade of good. During the first semester of that academic year, he received the grade of unsatisfactory in mathematics, which he later corrected. This poor grade in mathematics was most likely due to his two months of illness. Nikola passed his final graduation examination on July 24, 1873. The inspector at the examination was the natural scientist and zoologist Zivko Vukasovic (1829-1874).

After his final examination, he returned to live with his parents in Gospic, disregarding the wishes of his father, Milutin, who wanted him to stay away from the cholera epidemic raging in Lika at the time. Nikola caught cholera and was bedridden for nearly nine months. After he recovered, he faced three years of military service in the Austrian army. Since he had changed his place of residence and was registered as living with his uncle, Toma Mandic, in Tomingrad near Gracac, he was technically an army deserter.

Nikola did not pursue a priestly vocation, as his father would have liked, but electrical engineering. A crucial role was played by his secondary school professor in Rakovac, Martin SekuliÊ, who was an excellent experimenter and constructor of physics devices. Nikola wrote the following about this: “I was very interested in electricity, under the influence of a physics’ professor who was an ingenious man and often demonstrated the basic laws with devices he had invented himself. I remember one device in the shape of a freely rotatable bulb with tinfoil coating, which was made to spin rapidly when connected to a static machine. It is impossible for me to convey an adequate idea of the intensity of feeling I experienced in witnessing his exhibitions of these mysterious phenomena. Every impression produced a thousand echoes in my mind. I wanted to know more of this wonderful force; I longed for experiment and investigation and resigned myself to the inevitable with an aching heart.” Tesla does not specifically mention which professor he was writing about but it can be inferred with certainty that it was Sekulic.

4. TESLA’S STUDIES AT THE POLYTECHNIC SCHOOL (JOHANNEUM) IN GRAZ AND PERIOD IN PRAGUE

Two years after passing his final secondary school examination and recovery from illness, at the age of nineteen he enrolled during the 1875/76 academic year at the polytechnic school (Technische Hochschule) in Graz, Austria, with a scholarship from the Military Border Territory. His father, Milutin, and uncle, Toma Mandic, also sent him some money.

The dean of the polytechnic school wrote the following to Nikola’s father: “Your son is a star of the first magnitude.” Nikola’s efforts in his studies affected his health, so the professor recommended that his

father remove him from the school because there was danger that Nikola would ruin his health with

excessive work.

Tesla enrolled conditionally in the second year of his studies because there was no scholarship and he was not able to pay tuition. Distinguishing himself by his work and results, he became closer to some of his professors, including his professor in theoretical and experimental physics, Jakob Pöschel.

During the second year of his studies, the polytechnic school in Graz obtained a Gramme dynamo. Tesla

wrote the following about it: “While Prof. J. Pöschel was making demonstrations, running the machine as a motor, the brushes gave trouble, sparking badly. I observed that it might be possible to operate a motor without these appliances. But he declared that it could not be done and did me the honor of delivering a lecture on the subject, at the conclusion of which he remarked: ‘Mr. Tesla may accomplish great things but he certainly will never do this.’” Tesla continued: “For a time I wavered, impressed by the professor’s authority, but soon became convinced I was right and undertook the task with all the fire and boundless confidence of my youth. I started by first picturing in my mind a direct-current machine, running it and following the changing flow of the currents in the armature. Then I would

imagine an alternator and investigate the processes taking place in a similar manner. Next I would visualize systems comprising motors and generators and operate them in various ways. The images I saw were to me perfectly real and tangible. All my remaining term in Graz was passed in intense but fruitless efforts of this kind, and I almost came to the conclusion that the problem could not be solved.”

At the end of the second year of his studies, (1877), Tesla diligently passed his examinations but in the

third year, (1878), he became slack in his work. This may be due to the fact that he was unable to bring his problem regarding the construction of an electrical motor to conclusion.

After he lost his scholarship of 420 forints from the Command of the Military Border Territory at the age of 23, on two occasions he sought a scholarship from the Serbian Cultural Society in Novi Sad but was refused in 1876 and 1878. Therefore, he interrupted his studies and left Graz, also breaking ties with his family.

For a time, he lived in Maribor, where by chance, in an inn during a game of cards, he met an acquaintance. Allegedly, Nikola worked in Maribor for an engineer as an assistant and received a wage of 60 forints. Nonetheless, he was forced by the local authorities to return to Gospic, the place of his permanent residence, as an unemployed person. All of this was difficult for his father, Milutin, to accept and he died soon after, on April 29, 1879. Nikola then worked for a short time as a teacher at the Gospic secondary school that he had previously attended.

In early January of the year 1880, Nikola Tesla went to Prague at the age of 24. In his autobiography,

written in the English language, he wrote that he went to Prague to carry out his father’s wishes for him to complete his education at the university. However, there is no document showing that he was enrolled at either of the two colleges there or either of the polytechnic schools, German or Czech. It is possible that he attended lectures given by individual professors but there is no information on this. Regarding his sojourn in Prague, Tesla wrote that “it was in that city that I made a decided advance, which consisted of detaching the commutator from the machine and studying the phenomena in this new aspect, but still without result.”

5. NIKOLA TESLA IN BUDAPEST AND FRANCE

In 1881, Tesla began working at the Central Telegraph Office in Budapest. It was in this city that devised an electrical motor operating on the rotating magnetic field principle. Tesla had arrived at this invention by chance in February 1882, during a Sunday walk in the municipal park with his friend Antal Szigety, when he drew a diagram of this device in the sand with a stick. He showed his invention to the inspector-in-chief, Tivadar Puskás, who subsequently sent him to Paris, where he hoped to build his invention. However, there was no interest in the factory of the American inventor Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931), that was then designing and constructing direct current electric motors, under Edison’s patent, for France and Germany. Instead, Tesla made several changes in the existing electrical machinery.

Edison’s company sent him to Strasbourg in order to make repairs on a newly built power plant. It was there that Tesla constructed his first single-phase electromagnetic (asynchronous) motor.

6. TESLA’S LIFE AND WORK IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In 1884, Tesla left France to work in Edison’s factory in New York, where he stayed for one year and perfected twenty-four different types of electrical devices. Since he did not receive suitable compensation for his work, he left Edison’s company and, at the advice of several technicians and financiers, opened his own firm, the Tesla Arc Light Company.

At the time, he intended to construct new alternating current motors using company capital. However, the financiers did not approve because they were engaged in the construction and installation of arc lamps. In 1886, Tesla perfected the arc lamp and made a practical system for factory and street lighting. For his efforts, the company merely gave him some worthless stocks.

In the year 1887, he founded the Tesla Electric Company. In the laboratory of this enterprise, he constructed alternating current motors based upon his own ideas. That year, he filed four patents:

- in area with the rotating magnetic field,

- polyphase devices,

- induction motors,

- a long-distance electrical transmission system.

For the distribution of polyphase currents, Tesla constructed polyphase generators and transformers, and discovered the “star delta” system. This made it possible to produce electricity at the sites of its natural sources and then transmit it great distances to the places of consumption.

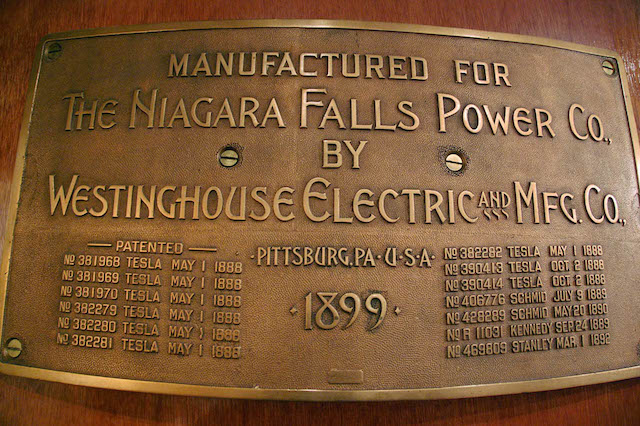

In the year 1888, Tesla sold his patents to the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. At the request of this company, during 1888 and 1889 he perfected a single-phase induction motor and adapted his entire system to the significantly higher frequency of 133 cycles because the company had been making lighting transformers for that frequency.

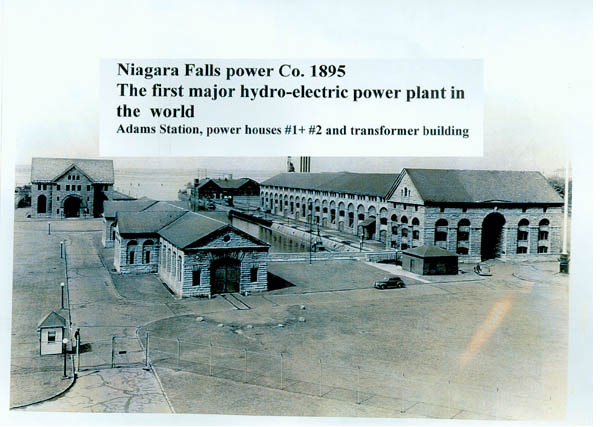

Tesla’s system for the transmission of electricity was presented for the first time at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, and in 1896 a hydroelectric power plant was built at Niagara Falls according to his system.

In the year 1889, he constructed an apparatus for producing high frequency electrical currents of 15,000 cycles per second. After that, using a special arcing construction in an electrical circuit, consisting of a low-frequency alternating current source, induction coil, condenser and spark gap, he obtained weakly damped oscillations. Sparks quickly ensued and continuous oscillations were generated. Thus, current of several hundred thousand cycles was obtained. Tesla transformed this current via his transformer into current of the same frequency but higher voltage. These are the so-called Tesla currents, which act physiologically and can be transmitted via a single wire. Tesla’s high frequency currents are used in medicine in diathermy and darsonvalization, and in chemistry for obtaining ozone. These currents achieve light effects based upon luminescence, and provide more economical illumination than incandescent light

bulbs. However, their most important applications are in radio technology.

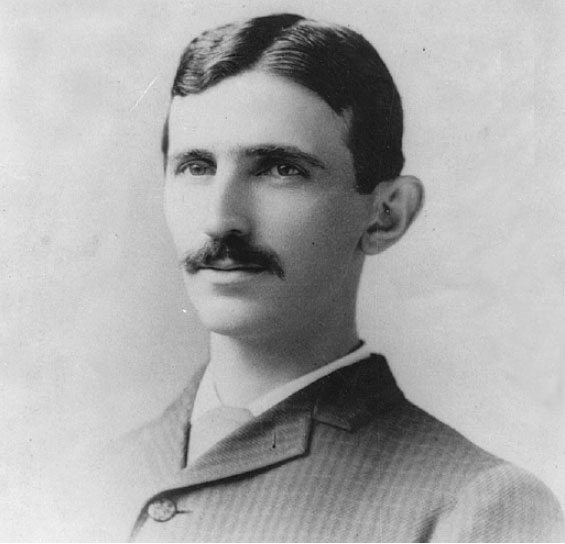

In 1892, Tesla conducted experiments in wireless transmission and in 1896 began to transmit signals at distances of 32 kilometers. He presented his radio-telegraph transmitter and receiver in 1897. Figure 5 shows Tesla from this period, at 39 years of age.

In the year 1898, he built a teleautomatic boat operated by remote control, that he demonstrated before a crowd at Madison Square Garden in New York City. That year, he demonstrated the need for resonance between the primary and secondary circuits of a transmitter and receiver. In 1899 in the state of Colorado, he transmitted signals wirelessly at a distance of 1,000 kilometers, and built a primary transmitter station. With this station, Tesla became the creator of radio technology.

Realizing after his first attempts that weakly damped oscillators were creating signal interference, he abandoned damped waves in favor of undamped electromagnetic oscillations. In this he surpassed

Guglielmo Marconi (1873-1937), who had achieved a signal range of 16 kilometers.

After testing in August 1899 and 1900, Tesla transmitted electricity by means of electromagnetic waves 30 kilometers from a 12 million volt source. In Long Island, he erected a 57-meter tower and engaged in the problems of the transmission of large quantities of electricity for household and industrial use. In 1917, an unknown perpetrator destroyed the tower with dynamite, perhaps at the orders of the general headquarters of the US Army.

Tesla completed work on over 100 patents, many of which are still awaiting practical application.

In experiments conducted during 1891/92, he used units with secondary circuits, a Tesla transformer and earth, i.e. all the essential parts of the transmitter that appeared ten years later.

The Italian engineer G. Marconi was using a wireless telegraph later than Tesla, in the year 1897. In 1892, Tesla held lectures in London and Paris on electromagnetic waves. The following year, 1893, he had developed his own system for wireless transmission.

7. TESLA’S PATENTS

It is not possible to obtain an accurate or complete picture of Tesla’s discoveries, inventions and constructions without inspection of his writings, notes and drawings.

Nikola Tesla patented ninety-nine of his inventions at the US Patent Office. These patents can be divided into the following groups:

- motors and generators – 36 patents,

- transformation of electrical power – 9 patents,

- lighting – 6 patents,

- high frequency equipment and regulators – 17

patents, - radio – 12 patents,

- telemechanics – 1 patent,

- turbines and similar devices – 7 patents,

- miscellaneous inventions – 11 patents.

He also published seventeen scientific and professional articles in journals:

- The Electrical World – 1 article,

- The Electrical Engineer – 4 articles,

- The Electrical Review – 11 articles,

- Electrical Experimenter – 1 article.

News of the death of Nikola Tesla was announced over the radio on January 7, 1943, by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York. He said that Tesla died a poor man but that he was one of the most useful people who had ever lived.

In order for Nikola Tesla to be recognized at the international level as a great figure in modern electrical

engineering, a study group of the the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) recommended that

the international unit of magnetic induction should be called a tesla. This decision was adopted and confirmed at the Eleventh General Conference on Weights and Measures, held on October 10, 1960 in Paris.